The past impacting

the present:

The enduring legacies of the transatlantic slave trade

Legacies

2007 marks the bicentenary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act (1807). The high-profile commemorations provide an opportunity for us all to reflect on, and respond to, the transatlantic slave trade by considering its enduring legacy. How does the fact that, over a four-and-a-half century period, millions of free Africans were captured, transported to the Americas and put to work as slaves impact on contemporary UK society? … on life today in North America and the Caribbean? … on life in Africa?

On the one hand, everyone living in the UK today benefits directly or indirectly from the historic trade in enslaved Africans. This is because some of the wealth created by the transatlantic slave trade was used to build (or repair) churches, cathedrals, public libraries, art galleries, theatres, town halls, schools, colleges, universities, canals, roads and railways. Other profits from the slave trade – made by those who owned, insured or built the slave ships, and those who smelted the ore to make the iron that was used to forge chains and shackles, as well as those who owned plantations or had a stake in processing and selling the crops sown, tended and harvested by slaves – provided endowments and scholarships which allowed generations of people with little money but great talent to push back the boundaries of art, literature and science.

On the other hand, precisely because the economy and culture we inhabit is contaminated by immoral earnings generated by the transatlantic slave trade and its associated industries, we share in the shame of those who went before us.

Maafa

Slavery is an ancient institution. It is mentioned in the Bible and was prevalent in Greek and Roman society. But the transatlantic slave trade differed from the Greek or Roman examples in two key respects:

- the scale of the operation - between 1440 and 1888, an estimated 20 million Black Africans were enslaved because of the transatlantic slave trade;

- (the barbarity of the operation - 50% of the 20 million Africans enslaved for the transatlantic slave trade died within two years of capture (0.9 million died at slaving ports on the African coast; 2.5 million died during the transatlantic voyage; 6.6 million died whilst being ‘broken in’ at ‘seasoning camps’ designed to prepare slaves for plantation life). A further 10 million Africans died in wars fought between African kingdoms as they vied to enslave each other’s populations in order to satisfy demand created by the transatlantic slave trade and, in so doing, increase their own wealth and power.

It is worth noting at this point that, from the 9th to the 19th centuries, the Arab-Islamic slave trade robbed Africa of an estimated 17 million people (9 million via the trans-Saharan caravan route; 4 million via the Red Sea; 4 million via the Swahili ports in East Africa). Between them, Europeans and Arabs systematically mined Africa of its human population. The Kiswahili word ‘Maafa’ (literally meaning ‘terrible occurrence’ or ‘great tragedy’) is sometimes used to describe this thousand-year ‘Holocaust of Enslavement’ or ‘African Holocaust’.

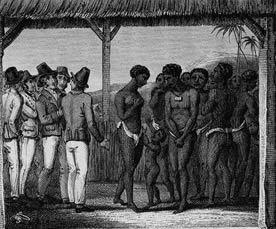

During the transatlantic slave trade, ships sailed from Europe to Africa to the Americas and back to Europe again as part of the Triangle Trade. When ships arrived at an African slaving port, commodities such as guns, brandy, rum, iron and glass beads would be exchanged for a human cargo. In the eyes of White traders, Black African slaves were just another commodity to be bought, transported and sold for profit; Black life was cheap and expendable.

Justification

A three-fold justification was given for the systematic dehumanisation and exploitation of Black people: economic necessity, racist theology and race science.

From the 15th century onwards, Western European powers desperately wanted to find people to mine, farm and build their American colonies. The transatlantic slave trade delivered large quantities of cheap slave labour from Africa to European colonies in the ‘New World’.

Theology was used to advance a pernicious, racist ideology. Bible passages were cited to support a belief that the enslavement of one race by another was consistent with God’s plan for the world. Genesis 9:25-27 was quoted to suggest that Africans were the cursed ancestors of Ham, Noah’s son, and hence condemned to an existence of perpetual enslavement at the hands of their peers. Some Christians also argued that, because the Bible links ‘light’ with purity and ‘dark’ with evil, light skinned people are inherently good whilst dark skinned people are innately bad.

Some historians argue that the escalation of the transatlantic slave trade coincided with the birth of the specious discipline of ‘race science’ which alleged that Black Africans had a smaller cranial capacity – and were, therefore, less intelligent – than other races. Some race scientists even argued that Africans were more like apes than human beings.

Africa today

In the West, Africa is all too often depicted as calamity-ridden and ungovernable. We are bombarded with images of corrupt dictators, gun-toting rebels, refugee camps and starving children. Some people argue that greater trade equality between Africa and Europe will help to bring peace and prosperity to Africans trapped by conflict and poverty. But, to what extent can 21st century Fair Trade redress the legacy of the most unfair of trades: the trade in human beings?

Europeans arrived in sub-Saharan Africa having already made up their minds that Africans were naive beings who possessed nothing and were in need of everything. Hugh Trevor Roper, the esteemed Regis Professor at Oxford, argued that Africa had no history until the arrival of the Europeans; the continent was an ‘area of darkness’ which needed the illumination of Europe. A careful perusal of history books reveals that very few Europeans arrived in Africa during the slavery epoch holding the belief that Africans had anything to teach them. Hence, to Whites, trading on equal terms with Blacks was anathema.

For a thousand years Africa was systematically depopulated: first by the Arab-Islamic slave trade, then by the transatlantic slave trade. The fittest and ablest of its people were used to develop the old economies of the Mediterranean, the Middle East, Western Europe and, subsequently, the emerging economies of the Americas.

If you are interested in becoming a foster carer, the first thing you should do is contact your local fostering service (either the social services department of your local council or an independent fostering agency), and arrange a meeting.”

|

But, as the respective slave trades waned – and before the continent could catch its breath – a new era of exploitation began. During the ‘scramble for Africa’ in the 19th century, the Western European powers promised Black Africans three Cs: commerce, Christianity and ‘civilisation’. In reality, colonialism turned out to be every bit as one-sided as the slave trades that preceded it. Whites – eager to find resources to fuel their industrial revolution – began plundering the continent’s mineral wealth. Belgium, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal and Spain each staked a claim. King Leopold II of Belgium even had the audacity to establish a private corporate state for himself in central Africa, but the inhabitants of his Congo Free State were anything but free.

If we are not careful and critical, we – like our European forebears – may find ourselves unquestioningly accepting a worldview that sees Black Africans as the hapless victims of cruel circumstance or, worse still, of fellow Black Africans. This is the kind of thinking that established and sustained the transatlantic slave trade; led to an era of colonialism; and perpetuates race-based inequality around the globe today. Our worldview is a legacy of the transatlantic slave trade.

The Church

The Church had a chequered role during slavery. Individuals such as Granville Sharp and groups like the Clapham Sect acted to oppose slavery, but the Church as a whole was ambivalent and inactive at best, and often pro-slavery in its stance. It took the established Church 199 years to make any significant statement of regret about its role in slavery, which included owning slaves and plantations as well as receiving gifts and patronage from slave traders and slave owners.

The Church in the UK failed the descendants of the enslaved Africans again when they arrived from the Caribbean after World War II to help reconstruct a war-damaged country. Many White Christians were aloof and unwelcoming; others were overtly racist. This unfriendliness was one of the reasons for the birth of ‘Black’ churches in the UK.

The marking of the bicentenary of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act (1807) provides us with ample opportunity to examine slavery’s continuing impact on our society. There is little doubt that the Church has an invaluable part to play in this work because anything that was part of the problem must be part of the solution.

Freedom for all

In former times, abolitionists fought to set slaves free but ignored the need to dismantle the structures that enslaved them in the first place. Two centuries on, we find that we are all – Black and White; African and European – shackled to the past … and to one another. This is the legacy we share.

For each and every one of us to be truly free, all must be set free: free from prejudice; free from discrimination; free from poverty; and free from inequality. This is the real story that needs to be told during the bicentenary celebrations. The struggle against slavery is still unfinished. This fight involves freeing people from modern-day forms of literal slavery and bondage, and liberating us all from the legacies which continue to blight lives and dishonour God.

Richard Reddie

Top Pic: Depiction of the successful slave rebellion in St Domingue. Pics courtesy of Anti-Slavery International

Second Pic : Africans exposed for sale as chattel slaves, �they are to be seen almost daily exposed for sale� like oxen or sheep�, from The West Indies as They Are by Rev R. Bickell (1825, p.19)

Back: Freedom Song

An extended version of this article was first published in the Summer 2007 edition of ACT Now, the membership magazine of the Association of Christian Teachers (ACT). Reproduced with permission. © 2007 Association of Christian Teachers. All rights reserved. |